CS180 Project 4a: Stitching Photo Mosaics

Part 1: Recovering Homographies

Homographies are used as transformation matricies to map points from one plane to another. We need to use homogenous coordinates to allow for more complex projections. You can use least-squares to solve for the homography, but I used SVD as it is a better way to avoid the case where H is near singular (making the SVD solution more robust than least-squares). The math is also shown below.

The matrix-vector multiplication is:

$$ \begin{pmatrix} x' \\ y' \\ w' \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} h_{11} & h_{12} & h_{13} \\ h_{21} & h_{22} & h_{23} \\ h_{31} & h_{32} & h_{33} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} h_{11}x + h_{12}y + h_{13} \\ h_{21}x + h_{22}y + h_{23} \\ h_{31}x + h_{32}y + h_{33} \end{pmatrix} $$The resulting equations are:

$$ x' = h_{11}x + h_{12}y + h_{13} $$ $$ y' = h_{21}x + h_{22}y + h_{23} $$ $$ w' = h_{31}x + h_{32}y + h_{33} $$To convert back to Cartesian coordinates \( (x_c, y_c) \), divide by \( w' \):

$$ x_c = \frac{x'}{w'} = \frac{h_{11}x + h_{12}y + h_{13}}{h_{31}x + h_{32}y + h_{33}} $$ $$ y_c = \frac{y'}{w'} = \frac{h_{21}x + h_{22}y + h_{23}}{h_{31}x + h_{32}y + h_{33}} $$Part 2: Warping

For warping, I found the homography using the source and destination points defined by the correspondences, and I used that to warp the source points to the destination points. I used inverse warping and nearest-neighbor interpolation.

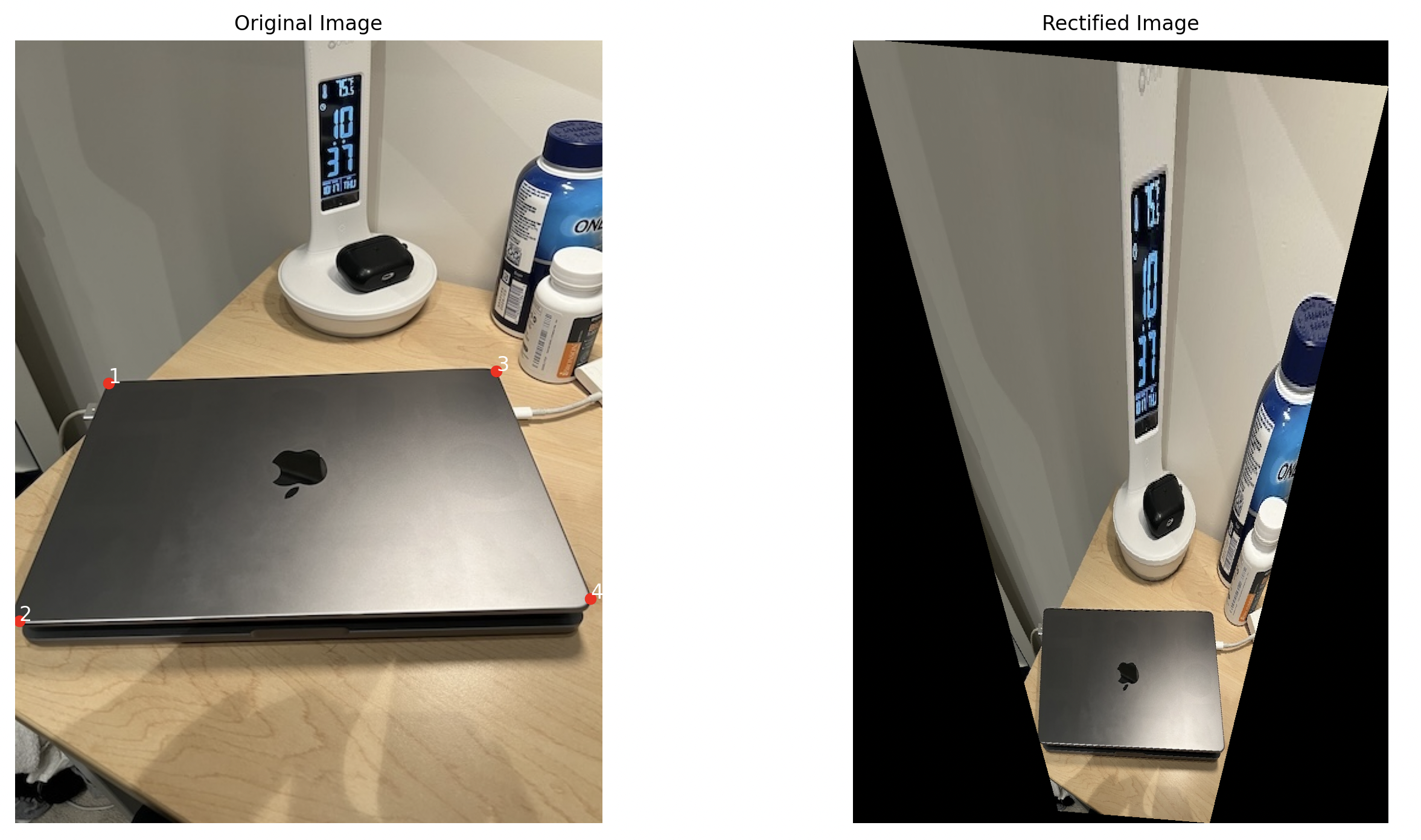

Part 3: Rectification

This part involves perspective changing the shape of a rectangular object in the input (which may be at an angle), and shifting it so that it appears like a flat rectangle in the output. I utilized the correspondence tool from last time. Results are show below.

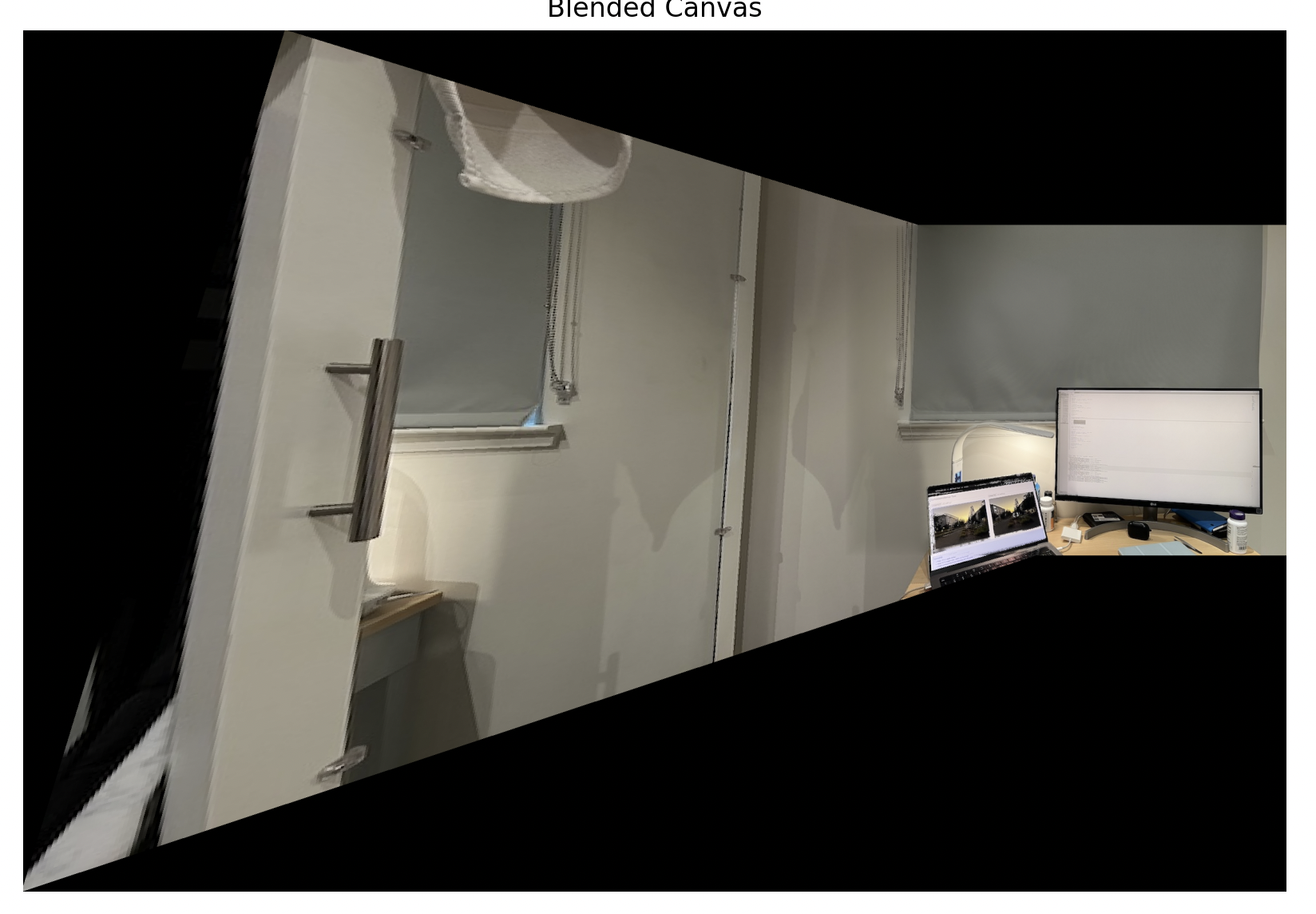

Part 4: Blending The Images Into a Mosaic

In this two-image mosaic process, there are two main steps: image warping and alignment, followed by blending the images to remove visible seams. To ensure that the combined images fit within the same frame, I created a larger canvas that is big enough to hold both warped_im1 and im2. This canvas accounts for any translation or displacement that occurs during the warping process, ensuring both images are positioned properly within the same coordinate space.

I created binary masks for both warped_im1 and im2. A binary mask is simply a black-and-white image where the white areas represent the visible portions of the image, and the black areas represent the background or unused space. To create these masks, I converted the images to grayscale and then applied a thresholding technique. Pixels above a certain threshold are set to 255 (white), while others are set to 0 (black). This process allows me to distinguish between the foreground (image content) and the background. I computed distance transforms for each mask. A distance transform calculates, for each pixel, how far it is from the nearest boundary (edge of the image content). The result is a smooth gradient of values where pixels near the edges of the image content have a value close to 0 (since they are right at the boundary) and pixels further away from the edges, towards the center of the image content, have values closer to 1.

The next step was to calculate an alpha mask. If dist_mask2 is larger, the pixel will primarily be taken from im2. In areas where the images overlap, the alpha mask ensures a gradual blend by weighting the two images according to their relative distances from the edges. I preserved the non-overlapping areas by directly copying the content from warped_im1 and im2 into the final canvas

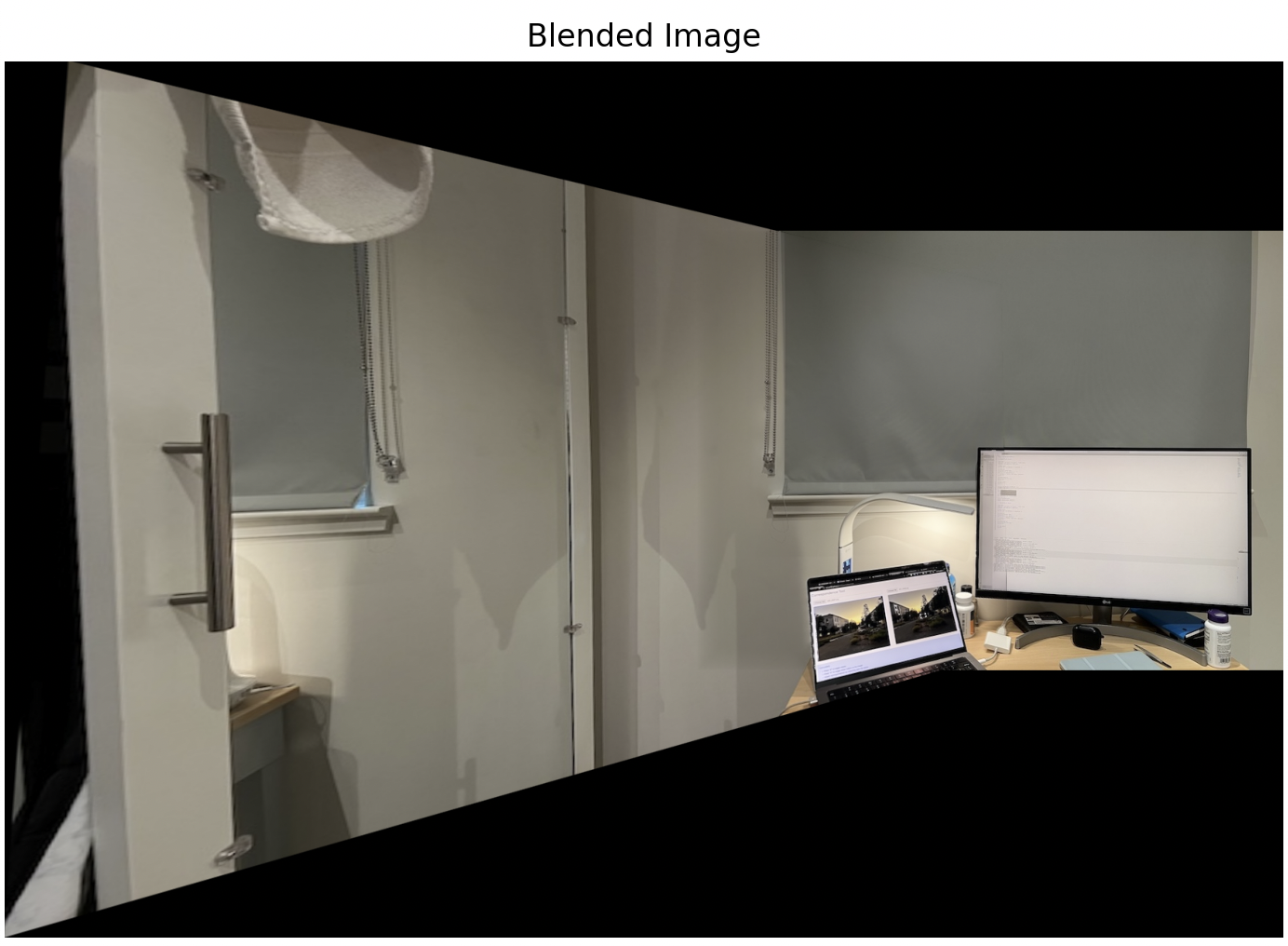

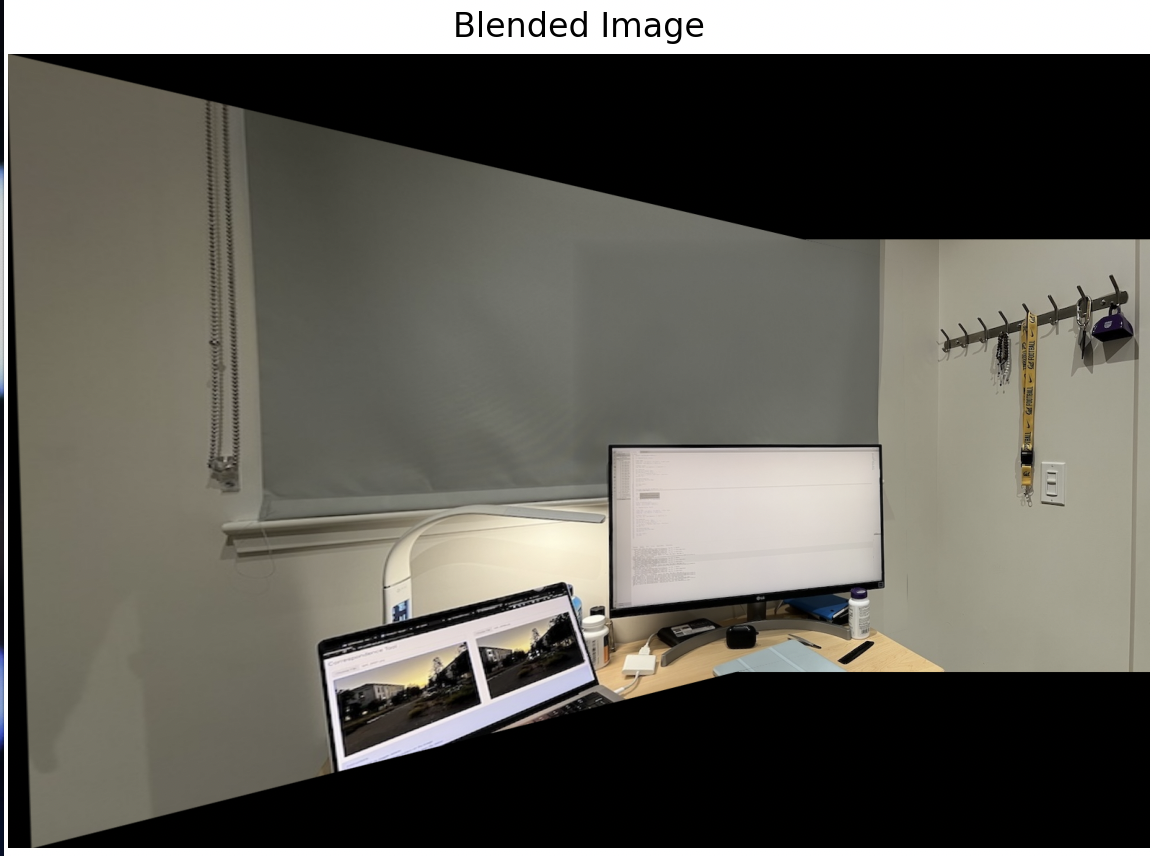

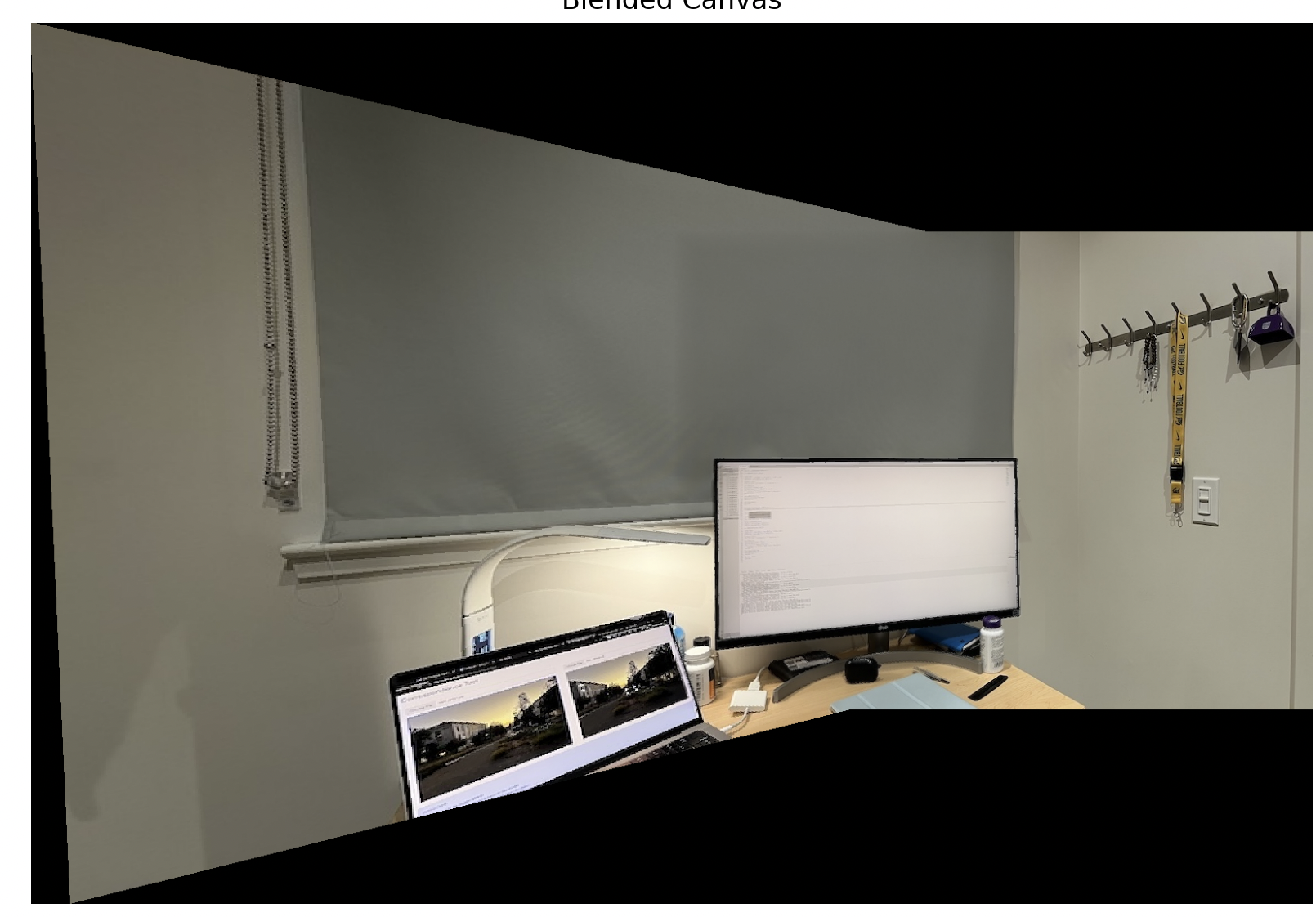

$$ \alpha = \frac{{\text{{dist_mask1}}}}{{\text{{dist_mask1}} + \text{{dist_mask2}} + \epsilon}} $$These are the close ups of the panoramics.

These are the side by side of the source images + panoramics.